Inclusive design is often confused with simply designing for people with disabilities. However, true inclusive design is much more than this — it is about designing for as diverse a range of people possible. It is a philosophy that encourages us to consider how size, shape, age, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, education levels, income, spoken languages, culture & customs, and even diets shape the way we interact with the world. More importantly, it is about designing products and services in light of this understanding.

Designing for Mr Average

Not so long ago, the term ‘inclusive design’ did not exist. There was also a view among many that one-size may fit all, and designing for an ‘average man’ was good enough.

Today, we are still surrounded by products that only work well for a limited range of people. Some are hard to interact with if your hands are small, or you have limited strength or dexterity. Others don’t fit because of the shape of your nose or torso, others are biased toward those who speak a certain language or follow certain customs.

It is not always completely clear why products are designed to exclude people. Often, it’s a perceived efficiency-thoroughness trade off — a variant of the 80:20 rule, that crudely suggests that you can get it right for 80% of the people for 20% of the effort, while it takes a further 80% of the effort to get it right for the remaining 20%. However, much of the time it is simply that the designers haven’t thought enough about the diversity of the people who wish to interact with the product that they are designing, often because it’s not in the culture of the company.

How big a problem is this?

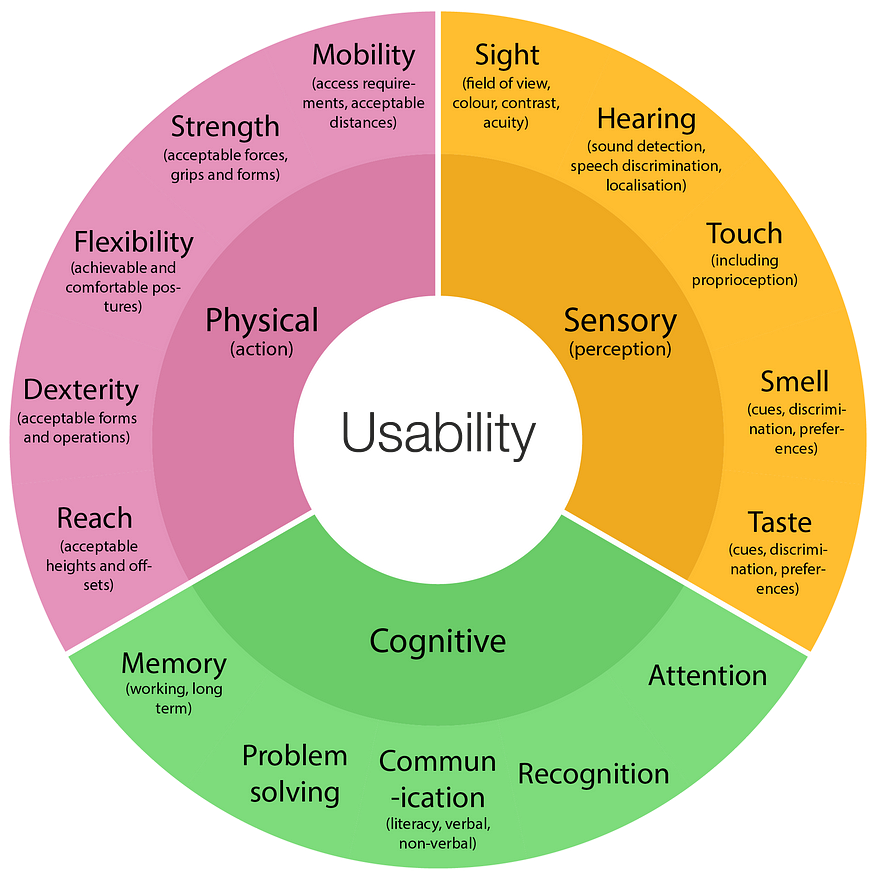

It is also often the case that the number of excluded people is dramatically underestimated. Capabilities are frequently thought of in binary terms. For example, you can either see or you can’t, or you can hear or you can’t. In reality, our sensory, cognitive and physical capabilities all tend to sit on a long spectrum. Some on this spectrum are excluded altogether, while a much greater number are inconvenienced. To complicate things further, these spectrums are rarely linear; in many cases, they are multi-dimensional.

Taking sight as just one example, the range of capabilities is incredibly complicated. Some people can see perfectly well without any form of correction, others require spectacles to see things that are far away or very close, others take longer to shift focus, or perhaps struggle in low light, some are unable to perceive colour, while others have a limited field of view (tunnel vision, or only peripheral vision), or monocular vision. The remaining senses are just the same, whether it is hearing touch, smell or taste — some people may have no sensation at all, however, a much larger group have different capabilities on multi-dimensional spectrums.

Physical capabilities are very similar. These include the kind of capabilities that we might naturally think about when we consider inclusive design, such as mobility, strength, flexibility, dexterity and reach. Just like our sensory capabilities, they each lie on a spectrum.

Our cognitive abilities also lie on a spectrum, and it’s not quite as simple as a link to IQ. Some people may have exceptional memories, problem-solving skills, communication abilities, recognition or attention. However, our capability in one aspect is rarely an accurate predictor for another.

To complicate things further, our capabilities are rarely fixed. As we become tired or fatigued, our capabilities may drop off. Likewise, things change as we age or as a result of events in our lives, perhaps some form of trauma.

Downhill from forty

The old adage ‘it’s downhill from forty’ is not strictly true, in terms of our capabilities, it is actually more like mid-thirties! In early childhood, our sensory, cognitive, and physical capabilities improve very quickly. We master our senses at a relatively young age, while it typically takes much longer until we reach our peak in terms of physical and cognitive capabilities (in our early thirties). However, by our mid-thirties we are broadly at our peak on all of these, from then on we tend to start to see a general degradation as we age. By the time we reach retirement age, strength may be 50% of its peak, we also tend to shrink (by around 5%), while our sensory abilities also tend to deteriorate. Eye reaction time doubles, we require around twice as much light to read, we lose high-frequency hearing, and our sense of taste and smell become much less sensitive — often resulting in older people using much more salt, pepper and flavourings in cooking.

However, we are increasingly remaining in work for much longer. As such, the role of inclusive design is becoming more important if we wish to remain an efficient and effective part of the workforce.

Why design for a more diverse market?

The ethical case for inclusive design is easy to understand. Most of us want to live in a world where we all have an equal chance of engaging with society, participating in different activities, living independently. With an ageing population is most parts of the world, it also makes a good case at a societal level. But it’s a philosophy that also makes great business sense, and one that is embraced by some of the world’s leading companies to develop a larger customer base, improve customer satisfaction, reduced returns & servicing, increased brand reputation, and improved staff morale.

Perhaps the most credible business case is designing products that a greater number of people choose to buy and remain happy with — largely because of a greater fit with their capabilities. When thinking about capabilities it’s useful to think of them on three levels:

1. Permanent (e.g. having one arm)

2. Temporary (e.g. an arm injury)

3. Situational (e.g. holding a small child)

The market for people with one arm is relatively small, however, a product that can be used by people carrying a small child (or using one of their arms for another task) is much larger. As such, designing for the smaller market of permanent exclusions is often a very effective way of developing products that make the lives of a much wider group more flexibility, efficient and enjoyable.

Doing it…

Given the range of human capabilities that a designer has to consider, it is perhaps possible to understand why it is an area that is often overlooked. However, inclusive design does not have to be too taxing, particularly when it is embedded as a natural part of the design process.

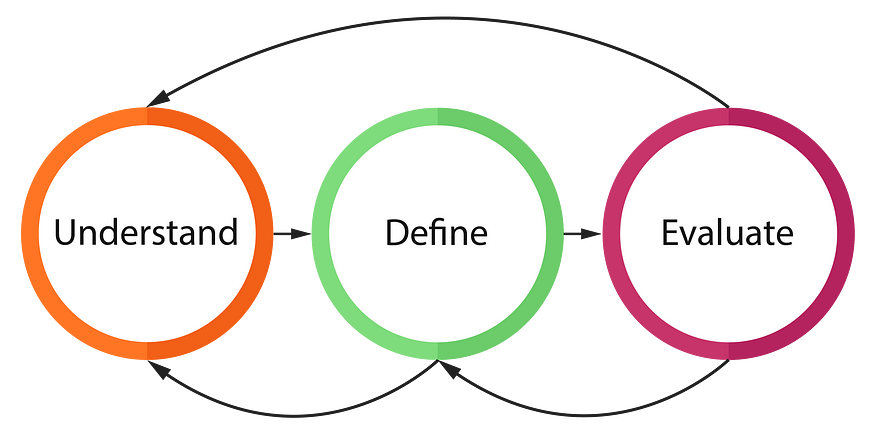

The first step on the path to designing more inclusive products is to understand where the current challenges are. The diagrams above can be useful prompts for this — firstly by thinking about the demands that the device places on people at a sensory, cognitive and physical level, and secondly by considering which aspects of human diversity may influence the interaction with the device (these are prompts rather than an exhaustive list).

The second step is to make informed decisions about the product specification. This includes balancing the needs of inclusion with other measures of system performance (such as efficiency, efficacy, safety, flexibility, and satisfaction). At the early stages of the design, the specification should always be seen as a ‘living document’ that should be refined and updated as the design matures.

The task does not end here however, the remaining step is to continually test and evaluate the design throughout the design process. In reality, this means testing against the specification (and relevant standards) but also testing with as diverse a range of users as possible. While much can be done based on methods and tools, there really is no substitute for testing with people.

Understanding how to make the product better is, of course, just one part of the challenge. Getting more inclusive products to market relies on the buy-in of the wider product team — a commitment to design better products that are appreciated and valued by a diverse range of people and, by doing so, achieve better commercial success.